WRITTEN BY SARAH TANGUY

Korean-born Jae Ko studied at Toyo Art School and Wako University in Tokyo, where she earned a BFA ni 1988. len years later, she completed her MA at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. Since 1985, she has participated in group and solo exhibitions throughout the United States, as well as in Austria, Germany, japan, and the Netherlands.The recipient of several awards, including a Pollock-Krasner grant in 2001, her work can be found in the Washington, DC, collections of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, among others. Presently, she divides her timebetween Washington, DC, and Piney Point, a small agricultural community on the tip of Maryland's Western shore, where the Potomac and the St. Mary's River join the Chesapeake Bay. In college, she studied all

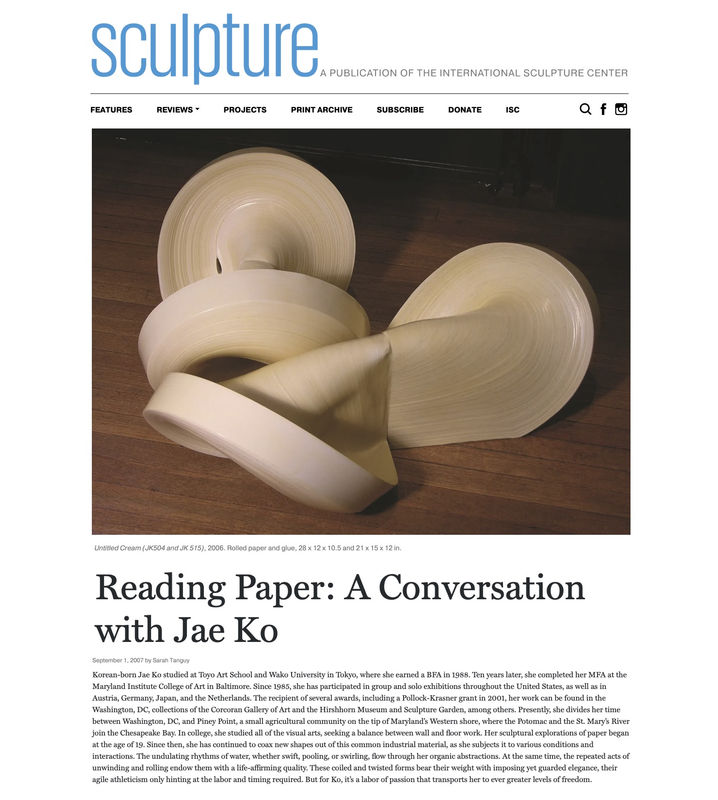

of the visual arts, seeking a balance between wall and floor work. Her sculptural explorations of paper began at the age of 19. Since then, she has continued to coax new shapes out of this common industrial material, as she subjects it to various conditions and interactions. The undulating rhythms of water, whether swift, pooling, or swirling, flow through her organic abstractions. At the same time, the repeated acts of unwinding androtting endow them with a life-affirming quality. These coiled and twisted forms bear their weight with imposing yet guarded elegance, their agile athleticism only hinting at the labor and timing required. But for Ko, it's a labor of passion that transports her to ever greater levels of freedom.

Sarah Tanguy: When did you start using paper?

Jae ko: I've been using all types of paper since I was in college, starting with rice paper, newspaper, books, crepe paper, adding-machine tape, butcher's paper- but never toilet paper, napkins, paper towels, or that kind of thing.

ST: What attracted you to paper?

JK: That's a very good question. Paper is always with you. Anywhere you go, you have paper, you see paper. I see paper as something you can really play with. also see it as possibilities, opportunities, and potential. Even one roll or one sheet of paper can create many shapes. You can also make a painting or a drawing on the paper.

SI: And what about adding-machine tape?

JK: I started using adding-machine tape in 1995. I had to make a small work for a project and didn't want to use art-store paper, so I decided on paper you can find at a wholesaler's to see what shape I could make without cutting. They had boxes of paper, and I said, "That's it, I can play with that."

ST: Did the rolled paper suggest the forms you initially explored?

JK: No, they're based on lots of different experiences. The tape comes intiny spools to fit ni the machine. Ihad to stretch my idea of how to work with this paper. At first, I started to unroll it and make a pile, but then I realized that it wasn't going to work. So l

ended up rewinding it and making a shape out of it.

ST: What was the process in the early adding-machine tape works?

JK: At the beginning, I didn't rewind the tape. I assembled many small spools of paper, made avertical cut that didn't go all of the way through, and put it randomly inside a four-by-four-foot metal frame tub. Then poured water in to see what would happen. I found that the spools didn't hold their shape because, as they absorbed water, they expanded and got squeezed. That's the basic idea, but it wasn't enough forme. So, I took acouple of large rolls, two- or three-foot-tall rolls, one foot in diameter, and made of brown wrapping paper. In the process of my work, I would screw two screws on the opposite pole of the roll through the width of the tape to retain some structure. Iwould then make an incision halfway through the length of the rol. This time, I soaked it in ocean water for several hours during the winter, close to here near Ocean City. I had to bury it in the sand, so nobody could see it, because I didn't have permission. High tide, low tide -I wasn't expecting to get this piece back, but held some hope and found it at a different place than where I had left it. The shape was totally changed with that much water and the action ofwaves going back and forth. Then I wondered how to bring this idea back into my studio. I bought the largest possible kid's plastic swimming pool, poured water into it, and began to soak all of

my paper in there. So that's how I got the idea for my previous work. And the most interesting thing is that I couldn't control the entire process. When the paper absorbs water, it rises by itself. With more study, I learned that I could adjust the tightness, I could make a space for the paper to squeeze into and then let it rise. This space makes a huge difference in achieving whatever I want to get. So half of the pieces go in the dumpster, and half I keep. A couple of years later, I could predict, "This one is going to be pretty much like that . I could read my artwork.

ST: How do you dry the paper?

JK: I tried to sun dry, heat dry, and air dry. The first two failed, but air drying worked, so I now use several fans to dry my wet paper.

ST: Do you make preliminary drawings?

JK: Before I make a piece, I have to make a scale drawing because I need to measure every single place before I start to roll the paper. I discard those drawings. But, Ido keep small drawing books.

ST: You started off with black works, then you introduced mono-chromatic ones, then pieces with several colors.

KJ: I'm not very attracted to color, so at the beginning, I always used black sumi ink. The ink comes from burning a tree and making ink out of the charcoal. Similarly, the paper itself is pulp, and it comes from a tree. So these materials fit each other. After I soak the paper in the ink, it comes out looking like burnt paper. Some people say that it resembles velvet, but it's more like burnt paper. It gives you that kind of feeling. After working with black for years, I started to miss color -the colors that are all around you. For about two years, I experimented with color. Saffron was too expensive, so I started to go into the forest, found black walnut shells, and boiled them. Indigo I had to order. It's more interesting for me ot use natural materials. Then I got bored with color and went back to black again. I started this new body of work in

2001. I hadn't had a show in Washington for four years. I was very busy with several solo and group exhibitions - I showed my work in Europe for the first time, where it was well received -and felt the need to take a break to develop a new body of work. I wondered, "Do I want to continue with adding-machine tape or experiment with a new material like metal?" I love the touch of paper, so I thought to change the shape, make the work more dimensional and take it off the wall. During a one-person show at Marsha Mateyka Gallery in 2006, I began creating floor piecs to accomodate my desire for more three-dimensional work. Before that, my work was between painting and sculpture.

ST: Exactly. I always associated you with making single, mostly symmetrical works, but all of a sudden there were groups. I also remember you saying that you improvise how you place them.

JK: It's like a puzzle. I see the overall shape as organic, and the pieces fitting together. I'm trying to re-create that concept of nature. Instead of a single pieces to be seen at 360 degrees, I can hide a piece or show it from another side.

ST: Your forms are more open now, less compact. In the earlier work, I always felt a very intense compression.

JK: That's a very good point. All of my previous work sat within the confines of the frame. Year after year, I felt jammed into the work. And I sensed that I had to get out of this mindset. That's why I started to roll and twist paper. So, maybe my next project will be looser. At the same time, I have to loosen myself. This is very critical. It's probably my background. Many Asians are well organized and very skilled with their hands. That's a part of me, and I want to break that rhythm. At least I have to try. While I'm working, I'm thinking about the next possibility of stretched material that I can use. It doesn't always have to be paper.

ST: There's also a change in surface and texture. The new work evokes saltwater taffy.

JK: To get the shape with the new work, I have to put glue directly on the surface, already mixed with ink. The black works have graphite powder in them; the red ones have Asian calligraphic red paint from a tube; and then for the cream-colored ones, it's only glue. The carpenter's glue has its own color. Sometimes, when I use too much glue, it looks like rubber and is very shiny. You don't see any detail in the layers of paper because it's all covered in glue. For two years, I struggled with this aspect of the work. There's still an element of fragility, but in order to show strength without the look of shiny rubber, I had to learn how to use this material.

ST: I consider your work as organically abstract and full of associations. Do you think about the original function of adding-machine paper is it primarily the natural reference?

JK: I don't really consider the function of paper. I consider the possibilities of every material that I see as an art material rather than its real purpose. When people ask, "What is this?" I say, "It's the paper you have in your pocket--adding-machine tape."

ST: Are you thinking of specific associations? I am reminded of the inner ear or seashells when I see these spiral forms.

JK: They relate more to my trips to the Inyo National Forest in California. Some of the Bristlecone pines are 5,000 years old. They live in a very dry climate and can take all kinds of weather. The trees don't grow straight; instead they create amazing organic, twisted shapes, like Hiroshi Sugimoto's objects. Each time I go there, I realize that I love this type of tree. But do I want to make a drawing, right now in front of this amazing tree? No. I never do that. If I make a drawing or take a photograph, it becomes that. Everything I see, I just file in my brain. Whatever comes out later, I can work with as mine. I also love architecture. I love bridges and their amazing shapes, what humans can do and how they push the limits.

ST: So, you're interested in structures?

JK: I'm interested in human-made and nature-made structures, but they're all mixed toether in my work.

ST: How does your work relate to the human form, in your gesture or your creative process?

JK: I don;t really factor the concept of the human form into my work. But it's in my brain file. When I see the human body, a man or a woman lying down, I see the shape. Sometimes I play with my hand. You can make all kinds of shapes with five fingers, or with two hands. My hands are right here.

ST: While movement and gesture have always been important, in your previous work, the movement was more ofa no-beginning, no-end internal loop. The new works are more open forms with a sense of acceleration and deceleration. I remember thinking that if I were an ant crawling around inside these spaces, I would be going really fast, as though on a rollercoaster. How do you see the change in movement?

JK: Yes, there is a kind of movement, and it has to be really fast to avoid the shape collapsing. You have to get it at just the right moment, hold it, start to put glue on it right away, and use a hair dryer. The first coat is the most critical. Otherwise, the shape doesn't take. The untitled red work is stretched as much as I could. It collapsed at least 10 times. You have to support it with heavy metal, hold it in one hand, and apply the glue very fast.

ST: In listening to you, I sense that themes grow organically out of how you make the work. Do you agree?

JK: Paper itself guides me - its limits, how much I can push and pull it. I want the viewer to figure out with me the ideas or themes in my work. That's why I keep making and changing the shapes until I get answers

or feel comfortable. Actually if I knew fully what I was doing, I wouldn't be excited. I always have questions.

ST: Do artists or aspects of your background influence you?

JK: Rolling or unwinding paper over and over again, same place, every day. It's my time to make myself empty. And that's probably my Asian background. I love Western artists too, like Richard Sera. His work is very architectural, very conceptual, and very

simple. But I also love Antonio Gaudi. He put his hand on every detail. I love them both. I think l'm in the middle.

ST: Can you give me a preview of your next body of work?

JK: One of the things l'm exploring is rolling the joint tape that's used in construction for plastering walls. The paper is very thick and has a beautiful color. And when I move around the paper, the shaded or dark part naturally shows up. I'm really enjoying experimenting. And at the same time, this paper makes me feel looser, more comfortable.

ST: I get a sense of freedom in your new work in contrast to a sense of gravity and weight in some of your previous work.

JK: The work is free, totally. That's what I want -the paper free of glue, of water, or o fthe frame. Paper itself has lots of emotions. You just have to read it.

Sarah Tanguy is an art historian based in Washington, DC.